Karen Bradley, the British government minister in charge of Northern Ireland, sparked outrage on 6 March when she said that killings by the security forces in Northern Ireland during the war years of 1968–1998 ‘were not crimes’.

The police and army killed around 360 people in Northern Ireland during that time, and they are linked to hundreds more deaths through their collusion with loyalist paramilitaries.

Bradley went on to say that the police officers and soldiers who took the lives of others were ‘fulfilling their duty in a dignified and appropriate way’.

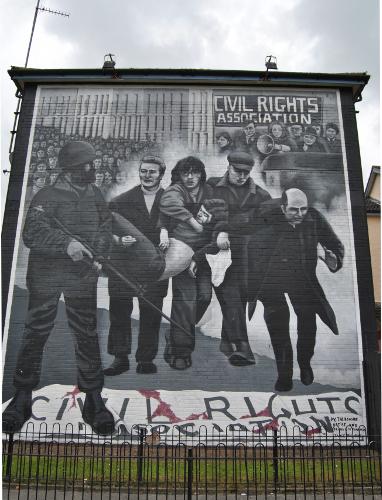

Before Bloody Sunday

Billy McGreanery told the Derry Journal he was ‘livid’ when he heard these remarks. His uncle William McGreanery was shot dead by a British soldier as he was walking near an army observation post in Derry on 15 September 1971.

He added: ‘That was an absolute insult to every family affected by the Troubles that has incurred loss.... There are inquiries and cases still ongoing... and it is disgraceful they are dragging these cases over decades and decades and decades, and I believe it’s a waiting game – they are waiting for the soldiers to die.’

In 2010, the British government’s Historical Enquiries Team, set up in September 2005 to investigate unsolved murders (and wound up in 2014), found that William McGreanery was not a member of any paramilitary organisation, was not carrying a firearm of any description, and posed no threat to the soldiers in the observation post who shot him dead on 15 September 1971.

The local police recommended that the soldier who fired the fatal shot be prosecuted for murder. This was overturned by the attorney-general of Northern Ireland, signalling that British soldiers could kill without fear of punishment. The Bloody Sunday massacre in Derry came six weeks later.

Convicted

One of the difficulties of Bradley’s position was that four British soldiers have been convicted of murder.

It wasn’t until December 1984, some 13 years after the murder of William McGreanery, that we see the first such conviction. Private Ian Thain (then 19) was given a life sentence for shooting dead Thomas Reilly (22) as he ran away from Thain’s patrol in west Belfast on 9 August 1983. He had just been searched by Thain’s patrol and found to be unarmed.

The judge said Thain had been ‘deliberately untruthful’ on the witness stand.

Thain was released after serving just two years in prison, and was taken back by the British army.

Two more murder convictions came on 10 February 1995, when Scots Guards soldiers Mark Wright (then 19) and James Fisher (then 24) were sentenced to life imprisonment for killing Peter McBride (18) as he ran away from their patrol in north Belfast on 4 September 1992. Again, he had just been searched by the patrol and found to be unarmed.

“Police recommended that the soldier be prosecuted for murder. This was overturned.”

The judge said that both murderers were ‘untruthful and evasive’, and Fisher had ‘deliberately lied’ during the trial.

Wright and Fisher were released on 2 September 1998 after serving six years of their life sentence, and they were taken back into the British army a few months later.

The fourth murder conviction, of Lee Clegg, was overturned on appeal. Clegg (then 21) was part of a four-man patrol in west Belfast in September 1990 that fired on a stolen car as it passed by and then drove away. Their bullets killed the two joyriders in the car, Martin Peake (17) and Karen Reilly (18).

Initially convicted of murdering Karen Reilly in 1993, Clegg was cleared of all charges in 1999. However, one of the judges also described Clegg’s testimony as a ‘farrago of deceit and untruth’.

Like the other three, Clegg rejoined his regiment – even before he was cleared of murder. He was released in 1995 after two years in prison.

These murder convictions are just the tip of the iceberg. There are dozens of cases, some of them involving large numbers of victims, where the police and army murdered unarmed and defenceless people, or sponsored the murder of unarmed and defenceless people by loyalist gunmen.

There is, for example, an ongoing inquest into the Ballymurphy Massacre, another precedent for Bloody Sunday, when soldiers, mainly from the Parachute Regiment, killed 11 civilians in west Belfast over two days in August 1971.

This is history that is still alive in Ireland and that British people cannot afford to forget.

-----------------------------------

Bloody Sunday

When the Northern Ireland public prosecution service finally announced on 14 March that a British soldier, just one, would finally be put on trial for the Bloody Sunday massacre, the decision was greeted with disbelief.

Kate Nash, whose 19-year-old brother Willie was killed on Bloody Sunday, told the Belfast Telegraph: ‘This is our worst day since Bloody Sunday. But we will dust ourselves down and the fight will go on.’

Derry journalist Eamonn McCann commented in the Guardian that both the Bloody Sunday families and the defenders of the British military would agree: ‘it is perverse and unfair that one low-ranking soldier should be made to carry the can for what happened in Derry 47 years ago’.

The decisions that led to the killings were made at a very high level, but they have not been exposed.

‘It was wrong’

The British government’s Saville Inquiry took 12 years and almost £200m to painstakingly investigate the shooting dead of 14 unarmed civilians during a protest march in Derry on 30 January 1972.

The inquiry refused to blame senior army commanders for the murders despite noting that, a few weeks before Bloody Sunday, the second-in-command of the British army in Northern Ireland, major general Robert Ford, recommended shooting ‘selected ringleaders’ of the ‘Derry Young Hooligans’.

Then British prime minister David Cameron summarised the conclusions of the Saville Inquiry in June 2010. He repeated facts that had long been known: none of the protesters who were shot by British soldiers had been armed, the first shot anywhere near the march was fired by the British army, and ‘in no case, was any warning given by soldiers before opening fire’.

Cameron went on: ‘He [lord Saville] finds that despite the contrary evidence given by the soldiers, none of them fired in response to attacks or threatened attacks by nail or petrol bombers.’

Cameron quoted the Saville report: ‘none of the casualties was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury, or indeed was doing anything else that could on any view justify their shooting’.

The prime minister apologised on behalf of the British government, and said: ‘What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong.’

Soldiers lied

When we turn to the Saville report itself, we find harsh criticisms of individual British soldiers. For example: ‘As to the further shooting in Rossville Street, which caused the deaths of William Nash, John Young and Michael McDaid, Corporal P claimed that he fired at a man with a pistol; Lance Corporal J claimed that he fired at a nail bomber; and Corporal E claimed that he fired at a man with a pistol in the Rossville Flats. We reject each of these claims as knowingly untrue. We are sure that these soldiers fired either in the belief that no-one in the areas towards which they respectively fired was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury, or not caring whether or not anyone there was posing such a threat. In their cases we consider that they did not fire in a state of fear or panic.’

Saville went on: ‘We take the same view of the shot that we are sure Private U fired at Hugh Gilmour, mortally wounding this casualty as he was running away from the soldiers. We reject as knowingly untrue Private U’s account of firing at a man with a handgun.’

There are other similarly detailed condemnations of other individual soldiers who shot unarmed civilians on Bloody Sunday.

Despite all the evidence collected by their own Saville Inquiry, the authorities have decided to charge just one soldier, known as ‘Soldier F’. He is being tried the murders of James Wray and William McKinney, and the attempted murders of Joseph Friel, Joe Mahon, Patrick O’Donnell and Michael Quinn.