As I write, two of my friends are in Afghanistan visiting the Afghan Peace Volunteers (APV) – a community of young peace activists in Kabul whose writings and short films (‘love letters from Kabul’) are deeply poetic.

As I write, two of my friends are in Afghanistan visiting the Afghan Peace Volunteers (APV) – a community of young peace activists in Kabul whose writings and short films (‘love letters from Kabul’) are deeply poetic.

I was reminded of the APV when reading this book. In the late 1960s, the US carried out a massive secret bombing campaign over the Xieng Khoang region of Laos. In just five years, thousands of people were killed and an entire ancient civilisation wiped out, under the most intense disposal of ordnance from the air ever conducted.

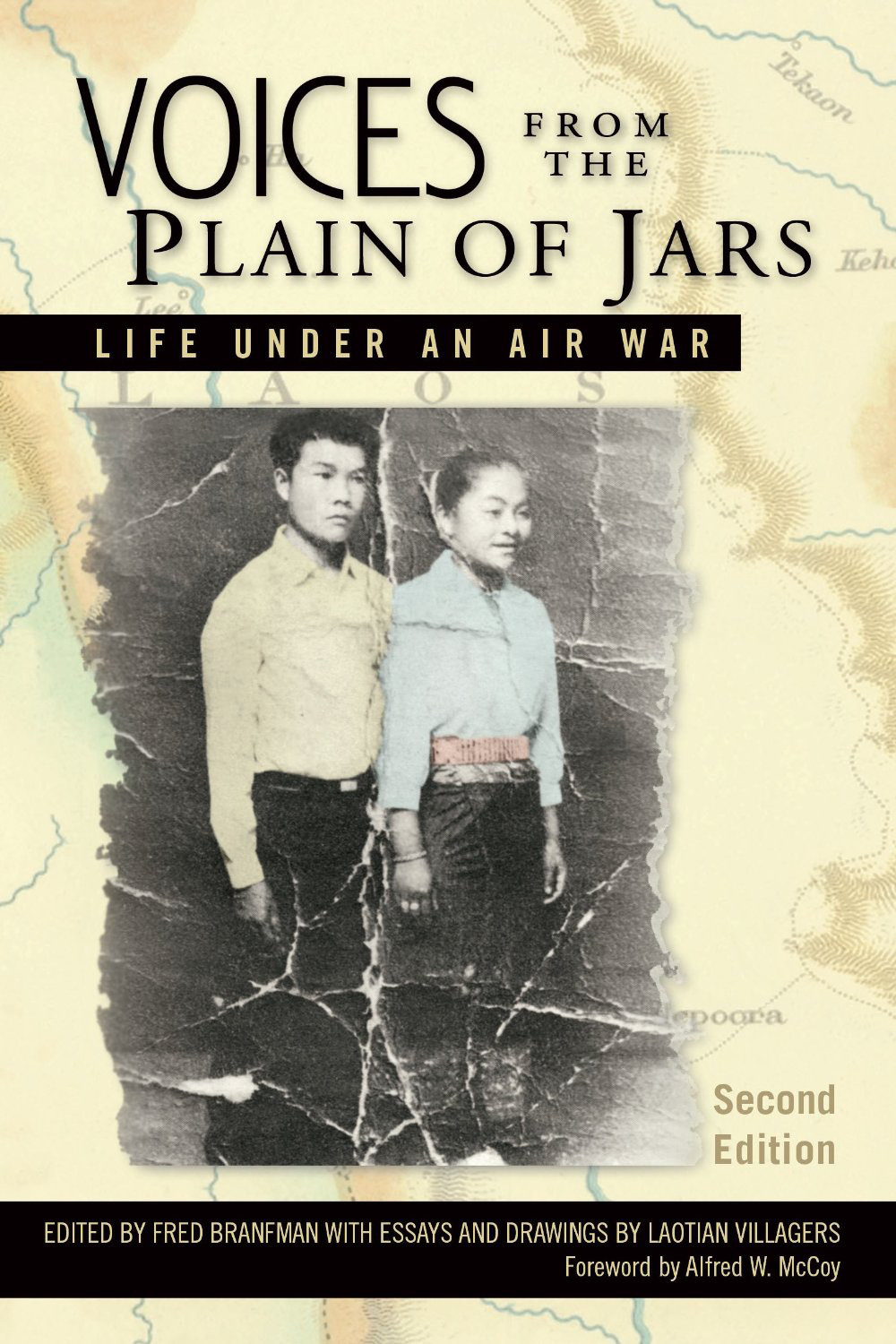

Half of this book is a moving collection of writings and drawings by some of the Laotian villagers who survived. The stories all begin with lovely lyrical descriptions of the homeland they have lost: the fertile landscape of the Plain, village life, local festivals, and the Buddhist monks who were the spiritual centre of life.

This was the Plain of Jars, an area of Laos that borders northern Vietnam and which had been inhabited for centuries. The region was no stranger to war and conflict, but enjoyed some stability following the 1946 withdrawal of the French colonial army, and an international neutrality agreement.

The Pathet Lao (communist) guerrillas came and brought gender equality and mutual aid, and trained villagers in medicine and basic skills such as reading and writing. Life was good. ‘But then the airplanes came, and bombed our dearly beloved land… destroying fences, fields, gardens, storage bins and houses’ – everything the villagers needed to survive.

At this point, the stories tell the same terrible tale of the civilian experience of war: the story of loss, trauma, terror and displacement.

First the villagers ran into the forests to hide, but, as the bombing intensified, they took to living in hand-dug holes. Even there, ‘death did not flee us for long’, with planes carefully targeting villagers in hiding.

Eventually the survivors were forcibly removed to refugee camps where they became sick – both physically ill and heartsick – unable to support themselves without access to their own land.

In the first half of the book, Branfman tells the story of his campaign to expose the US’s secret air war in Laos in the late 1960s, showing how secrecy and the use of remote technology (rather than ground troops) intersect to devastating effect.

It’s the methodology being effectively used today in the drone wars in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

By giving an accessible explanation of the history of the Laotian air war, from the perspective of one siding with the victims rather than either of the warring factions, Branfman makes this frame both easy to understand and relevant. He articulates a structure for understanding the drone campaign, with its extrajudicial executions and official obfuscations, that goes beyond the simplistic one-side-or-the-other debate that the mainstream media would have us engage in.

This is about understanding war from the point of view of those whose lives are ruined by it.

The pictures and words of the people who are the voices of what was the Plain of Jars make this more than a case study. They provide us with the moral of the story: the warmongers, our governments – who seek ever more secret methods – will continue to get away with it, if the voices of those beneath the bombs remain unheard.