Many of us have seen recruitment adverts for the armed forces popping up on our social media feeds, on TV and on the radio.

Many of us have seen recruitment adverts for the armed forces popping up on our social media feeds, on TV and on the radio.

Others will have come across recruitment stalls in their local town centres, perhaps with weapons on display for passersby – especially young children – to admire and handle.

If you are 16–24 years old, and from a low-income background, you are especially likely to be targeted with various kinds of military recruitment advertising in your daily life. Around £27 million of public money is spent on this every year.

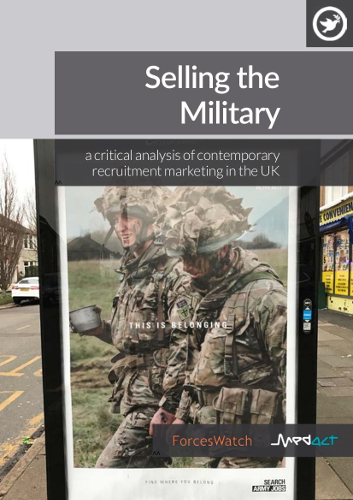

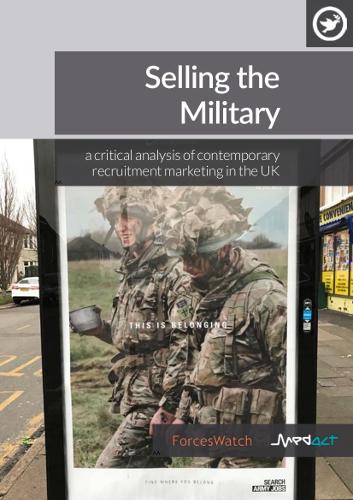

Military recruitment marketing sells self-improvement to young people. It presents the military as a career path full of opportunities and support, where diversity is championed. It promises friendship and a sense of belonging.

Some of the gaps in reality between recruitment marketing and lived reality for many personnel are explored in a recent report by ForcesWatch and Medact called Selling the Military.

This report argues that military marketing campaigns should be assessed not only in terms of their success in attracting recruits, but also by ethical and health criteria.

Since enlisting in the military can have life-changing consequences, we need to question if it is appropriate to target audiences on the basis of their youth and other vulnerabilities.

Fulfil yourself

Selling the Military also argues that it is unethical to promote self-fulfilment for people in this country against a vague backdrop of war and armed violence in other countries.

While the British military does take part in different kinds of activities like humanitarian relief, it is primarily a fighting force projecting British armed power in the world.

This is only fleetingly reflected in its recruitment advertising, where guns, fighter jets and military scenes flicker past. More prominent scenes show drinking, career development, friendship and sport. Weapons and war planes are presented as exciting and fun, and using them is seen as a way of achieving personal goals.

“If you are 16–24, and from a low-income background, you are especially likely to be targeted”

The same focus on military personnel, with weapons and military equipment glamorised and removed from context, is seen in wider military publicity.

Here, the aim is not only recruitment, but also to boost public support for the military and its missions. This will be seen at large on 20 June, the tenth annual ‘Armed Forces Day’.

Celebrating war

While events will be taking place all over, the main national celebration will be in Salisbury. It will include an enormous parade, a visit from members of the royal family and political leaders, and a military-themed family funfair.

I was at the national Armed Forces Day event last year, in Llandudno in north Wales.

There were rides, ice cream vans and food stalls mixed with arms company stalls, military recruitment advertising, tanks and weapon displays. Young children practised firing machine guns and had their faces painted in camouflage.

BAE Systems were giving away freebies and there were staged displays of military strength – from fighter jets to a simulated beach raid.

A dozen or so peace activists were slammed for holding up a banner, ‘War is Not Family Entertainment’, as they protested against what, in their view, was a distasteful and damaging glorification of war, militarism and armed violence.

On the minds of those peace activists was the damage caused by the British armed forces and British arms companies to people and countries around the world. They could not simply ignore the violent destruction of war beneath the spectacle of military might.

These same concerns are at the root of the creation of Armed Forces Day.

Re-militarisation

There was a significant lack of public support for recent wars, including vocal peace and anti-war lobbies. This led to a ‘militarisation offensive’ from around 2006, with the support of various political and military leaders, media outlets and pressure groups. This is detailed in the 2018 ForcesWatch report, Warrior Nation, written by professor Paul Dixon of Birkbeck College, London University.

The militarisation offensive aimed to shift the strong public support for troops into support for their missions; and to give the military more prominence and power in civilian society and over politicians.

“Opposition to militarism is weak in all the major political parties”

One part of the militarisation offensive is found in a 2008 document published by Gordon Brown’s government, which recommended ways to improve public support for the armed forces – including changing ‘Veterans’ Day’ (which began in 2006) into an annual ‘Armed Forces Day’ (the re-naming happened in 2009).

What are the results of the militarisation offensive? The military has increased its power over the government, and has vast support in the media, in much of civil society and among the public.

There are still recruitment problems, but cultural militarism is popular and military action, particularly when it is now ‘remote’ and comes without putting personnel at significant risk, is supported by many. Meanwhile opposition to militarism is weak in all the major political parties.

As David Gee writes in his book, Spectacle, Reality, Resistance, British militarism is in many ways a spectacle. It distracts and distorts, removing attention from the destruction of armed violence and imperialism.

The harsh reality is that British arms companies and the British military support leaders waging wars and committing human rights abuses around the world. Many civilians have been killed and displaced as a result of wars we have fought. Increasingly dangerous weaponry is being developed. Sustainable approaches to security are not prioritised.

Yet recruits are drawn towards the spectacle of travel, camaraderie and a high-flying career. In Selling the Military, RAF veteran Daniel Lenham describes an RAF recruitment ad as a ‘propaganda advertisement which sanitises all elements of militarism and tries to package its ethos into a fun, life-affirming, coming-of-age hedonistic utopia.’

Similarly, many people in the British public are drawn towards the family festivities, the marching bands, the nationalism, the assumed heroics, the impressive weaponry, and the demand that we should champion people who, it is claimed, ‘give their lives for our country’.