In my early teens I picked up a book from my sister´s shelves and quickly appropriated it as my own. Unknown to me then, it was to become a profound influence on diverse aspects of my life.

At that age I was already very interested in how things worked, and in dismantling and rebuilding anything that fell into my hands, from televisions to music boxes to steam engines. The book was all about alternative technology, full of images of wind turbines, eco-houses, biodigesters, compost toilets, and much more. Naturally it grabbed my attention. However, it was much more than a ‘how to’ manual, for, in the words of the back cover blurb, it saw ‘these new, liberating tools, techniques and sources of energy as part of a restructured social order, and (aimed) to place them directly in the hands of the community’.

Bottoms up

This framing of technology in a social (and ecological) context, as something emerging and controlled from the bottom up, was the radical message at the core of the book. This was the seed bomb sown in my head.

In the early 1970s, Godfrey Boyle founded a magazine called Undercurrents, described as the journal of radical science and people’s technology. In 1974, already with a substantial editorial collective in place, it was decided to produce a book that would encapsulate the philosophy of Undercurrents. The result was Radical Technology, published in 1976.

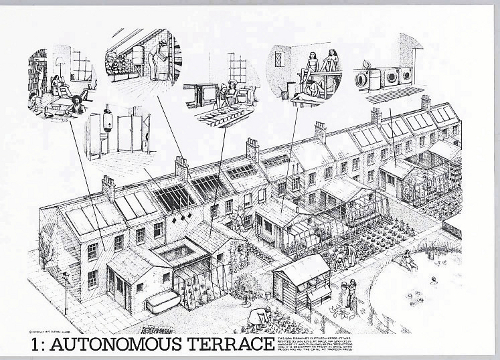

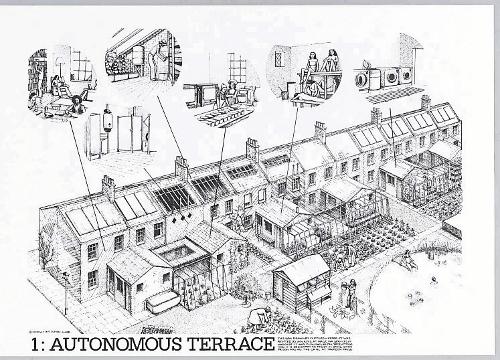

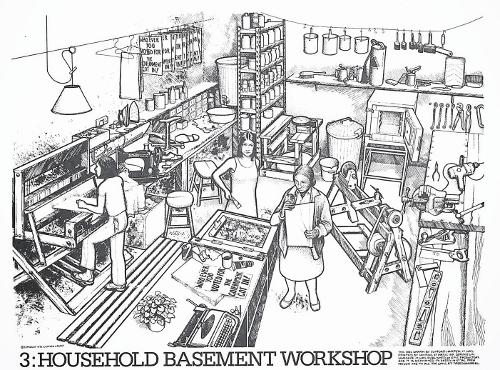

Within its 300 pages of closely-spaced type you find a collection of illustrated essays, widely varying in style, from the technical to the cosmic, and grouped under headings including food, energy, shelter, and communications. It’s all held together by the coherence of the Undercurrents editors, a strong overall design by Roger Hall, and, perhaps most importantly, by a series of stunning double page ‘visions’ drawn by Cliff Harper. I recently had a sort of revelation when I realised that in different phases of my own life I have recreated, with others, the visions shown in Harper’s images, from a housing co-operative in a terrace, to a community workshop, to an autonomous market garden.

Forty years on, a number of the original editors and contributors decided to organise a gathering to celebrate the anniversary, consider the legacy of this pioneering book and examine what traction its ideas have in a world increasingly looking ecological disaster in the face.

Around 60 people gathered in Bristol from 2 – 4 September to revisit Radical Technology. The majority were of that 1970s generation, including many of the original contributors, with, sadly, comparatively few younger faces around. The first day was one of reflection, with original contributors and others assessing how well the book has aged, and how many predictions had come true (although Godfrey Boyle was at pains to point out that the book did not aim to predict the future, rather inspire people to act in the present).

The following two days were more of a workshop format, trying to spin out scenarios for a sustainable future, For me they were less enjoyable than the first day. I suspect there was an age factor at work here: getting groups of 60-year-olds to envision a future four decades hence was always going to be a tall order. With 20-year-olds, it would have been a different matter.

Whole lotta history

The conference also boasted an exhibition space filled with publications, photographs, and artwork from the Undercurrents era, and this brought its own revelations. For instance, Comtek (short for ‘community technology’) was a festival showcasing alternative technology that began in Bath in the early 1970s. By 1975, it was a 10-day event involving over 150 groups. Another archive dealt with Street Farm (see PN 2578–2579), a London-based collective of anarchist architects whose output included what was arguably the first ecological house, built in Eltham in 1972.

My love of this book is really born of personal circumstances: it caught my eye when my young brain was at its most active and it never really left my imagination. What young people today need are such inspiring visions of a positive future, in whatever form they come, but visions we must have for we cannot build what we have not imagined.