Most people in Britain, I suspect, know little or nothing about women’s struggle for the vote here. For those who know a little, I would guess that the suffragettes would be top of the list of recognised names, followed by Emmeline Pankhurst and Emily Wilding-Davidson.

They might also recognise the name of the non-militant suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett, but that’s probably about it. Sally Heathcote Suffragette, a collaborative effort by Mary and Bryan Talbot (Dotter of her Father’s Eyes) and Kate Charlesworth (The Cartoon History of Time), may be the perfect starting place to learn more.

Making brilliant use of the comics medium – especially through its clever but sparing use of colour – stand-out sequences include the eponymous Sally’s force-feeding, and a deputation of suffragists to No. 10 Downing Street, where the silhouetted women are slowly transformed into mice, while the PM becomes a cat. My 10-year-old daughter read it at least three times in the first week, and most readers will surely want to read it at least a second time, if only to extract the full juice from the meaty 18 pages of annotations at the back.

Emmeline Pankhurst is here in all her autocratic splendour, but the real hero and heroine of this account – which cleaves very closely to real events – are the much less well-known Emmeline (‘Pethums’) and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence.

After founding a dress-making establishment (Maison Espérance) – which offered a guaranteed minimum wage to its workers, a rarity at the time – in the late 1900s, in 1906 Pethums was ‘sucked into the whirlpool’ of the Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU), the suffragette organisation, by former factory worker Annie Kenney. She would later devise the WSPU’s famous purple, white and green regalia, and, in her capacity as WSPU treasurer, she helped to raise roughly £130,000 (£10m in today’s money) for the organisation. Along with her husband Frederick, she also edited the WSPU’s official newpaper, Votes for Women.

After a dramatic opening featuring a 1912 suffragette ‘outrage’ with a hatchet in Dublin and the expulsion of the Pethick-Lawrences from the WPSU, we are taken back to 1898, and the story of the suffragettes is told through the life of the (fictional) Sally.

Thus Sally witnesses Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst leave to commit the first act of ‘militancy’ in 1906; is brutalised and arrested by police at the infamous ‘Black Friday’ demonstration in London’s Parliament Square in 1910; takes part in the first night of mass window-breaking in November 1911; hears Emmeline Pankhurst at a packed meeting at the Albert Hall in 1912 incite ‘those... who can’ to take their property damage beyond window-smashing; and helps turn these words into deeds by burning down Lloyd George’s new house in 1913.

Along the way, she confronts sexual harassment in the workplace, is imprisoned for her activism, and finds love with a man named Arthur Burton.

At the same time, the Talbots don’t shrink from portraying the uglier sides of the movement. Though founded in 1903, it was the Pethick-Lawrence’s 1906 decision to finance the WSPU that allowed Emmeline Pankhurst to quit her job and move to London from Manchester. As one recent history notes, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence ‘defended suffragettes in court, was forcibly fed in prison, and spent much of his fortune on the WSPU before being bankrupted for the cause and blackballed from his club’. However, none of this spared the Pethick-Lawrences when they found themselves at odds with Emmeline and Christabel over tactics (the Pethick-Lawrences thought the escalation to arson was folly, throwing away the ‘immense publicity and propaganda advantage’ achieved by earlier actions). The pair were summarily expelled from the WSPU, though they remained remarkably un-bitter about the experience (Emmeline and Christabel ‘cannot be judged by ordinary standards of conduct’ and ‘those who run up against them must not complain of the treatment they received’, Frederick later asserted).

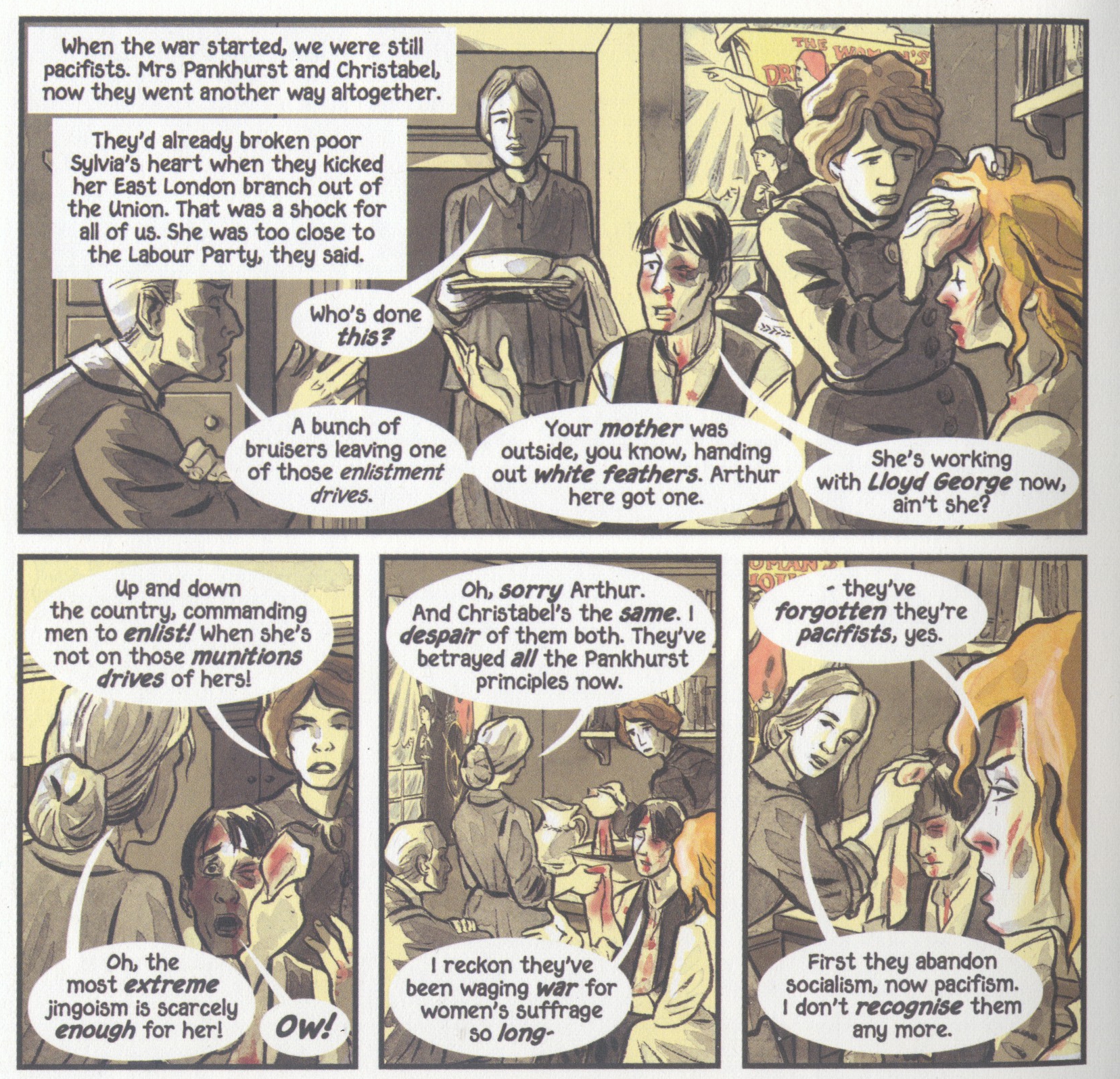

Like the non-militant movement, the militant suffragists split over the First World War. Famously, Emmeline and Christable Pankhurst halted their suffrage campaigning and went on recruiting drives around the country, while Sylvia kept the suffrage flame burning – and opposed the war – in the East End of London. Like Sylvia, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence opposed the war, taking part in the 1915 Women’s Peace Conference in the Hague, and leading a crowd of soldiers to No 10 in April 1919, in opposition to the ongoing ‘hunger blockade’ against Germany. Sally, naturally, opposes the war.

Recent scholarship has reassessed the role played by the WSPU in winning the vote.

In his 2000 book examining the half-century of suffrage campaigning prior to 1914, historian Martin Pugh argues that ‘the early emphasis on a parliamentary approach was both rational and successful’, that ‘the 1890s proved to be the decade of breakthrough for the suffragists’, and that the formation of the WSPU ‘was in some ways a symptom of the improving fortunes of suffragism rather than simply a cause’.

Moreover, he argues that the ‘central explanation’ for the movement’s eventual success lay more in the non-militants’ expansion into a mass movement, their alliance with the Labour Party, and their ‘attempt to develop a working-class base’ in the years immediately before the outbreak of the war.

Still, Pugh notes, the suffragettes remain ‘one of the heroic initiatives of modern history’. This book – suitable for ages 10 and over – is a fitting, and very welcome, tribute to them.