Back in 2008, the 24-year old Plane Stupid campaigner Dan Glass was invited to Downing Street to receive an award and took the opportunity to superglue himself to the then-prime minister, Gordon Brown.

But Dan’s life as a campaigner neither began or ended with eco-activism.

Dan was a queer school kid who came out after Section 28 – which prohibited the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ by local authorities – became law in 1988.

Dan writes about how he would ‘slink out on the night bus to Soho and… wake up next to some guy called Barry in Bedfordshire at 6 a.m., just in time to leg it to school. Hiding in the train’s toilet, STD-rich but financially poor, it wouldn’t be long before I hit the jackpot and got HIV. I pondered killing myself before the state could knock me off first. I could barely spell AIDS, let alone understand what it meant.’

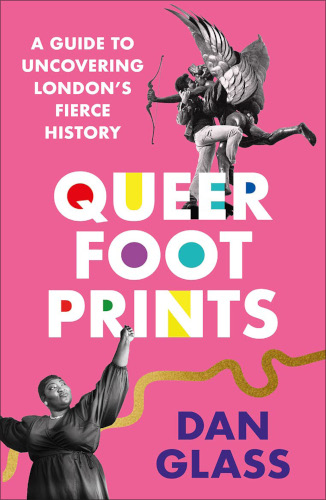

Most of Queer Footprints is nowhere near as explicit or autobiographical, but Dan’s voice as a queer Londoner is present throughout the narrative.

His motivation to write this guidebook was his realisation in 2014 that queer venues across London were closing down and, with them, queer history and heritage would be lost.

Dan was the driving force behind the campaign to recognise the iconic queer pub, the Joiners Arms on Hackney Road, as an Asset of Community Value.

The book is divided into eight long walking tours, from Soho to Ladbroke Grove, and 24 ‘mini-minces’ starting with the Highbury Fields cruising ground and ending with drag nuns can-can dancing and releasing mice into the audience at a Christian Festival in a Storey’s Gate church.

A walking guide is a book that can be entered from any chapter, and the history of the queer capital is absorbed as you flick through the pages – supported by an index which lists the Fagamuffin Bloc Party and the Famous Five, Chaka Khan and the Kray brothers.

Dan is inclusive and inter-sectional in his choice of histories and civil rights campaigners. Claudia Jones’ role in creating the Notting Hill Carnival is celebrated and references to the Black Panther parties (British and US) appear throughout the guide. Even princess Di is acknowledged for her HIV campaigning.

The Gay Liberation Front is a strong theme. The organisation’s time as a tenant in the basement of 5 Caledonian Road (home to Peace News and Housmans bookshop) is recalled by activist Andrew Lumsden:

‘GLF was a dandelion which grew, flowered and then degenerated into a fluffy but insubstantial head full of seeds which were then blown by several gusts into new areas of the meadow…. [In 1970,] We discussed “do we want membership?” and everyone responded “No!” It was a “dis-organisation”. People got involved and developed a sense of self-confidence and pride and then were able to go on and do things they never dreamed were possible. Nobody came into the GLF and remained the same….’

LGBTQIA+ communities have had to campaign against queer-bashing, nail-bombs and AIDS-driven homophobia, but the creative and inspirational responses devised to counter brutality and bigotry have brought people together and built support from allies.

No guidebook can cover everything, but this is a brilliant attempt at a comprehensive and engaging guide to London’s activism from a queer’s eye view. The illustrated maps by Mark Glasgow introduce each chapter and help to locate the sites of interest.

Histories, herstories and queerstories will always expand.

In his introduction, Dan encourages readers of the book to take inspiration and document the queerstory of where they live and walk. He also recommends reading the book in public – and buying a copy for the biggest homophobe in your life, in the hope that they’ll end up dancing to Donna Summer!