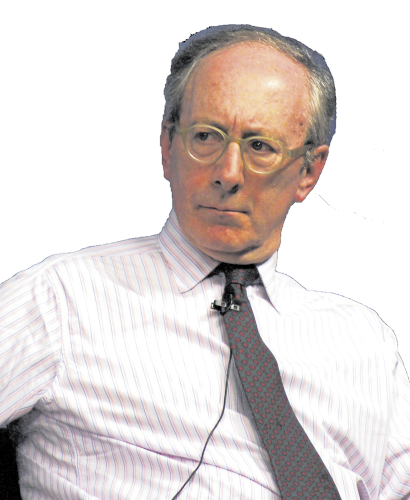

Some 30 years ago, a British defence secretary told the world that Britain wanted to be able to launch a ‘limited nuclear strike’ at an enemy in order to deliver ‘an unmistakable message’ of its willingness to defend its ‘vital interests’. That was Conservative MP Malcolm Rifkind, on 16 November 1993, admitting some nuclear ‘credibility’ problems.

His words become clearer if we turn back to the 1991 war on Iraq, where one of the big surprises was that the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein, did not order the use of chemical weapons against British and US forces.

The head of the RAF, sir Brendan Jackson, boasted in 1992: ‘Uppermost in his mind must have been the consideration that one weapon of mass destruction can be countered with another – and he could hardly have doubted that tactical nuclear weapons might have been in the area.’

Jackson then explained the Rifkind Doctrine described above: ‘It is interesting to reflect that in such a conflict, sub-strategic capability deters, when strategic capability with its heavy footprint could be more easily discounted by a cunning dictator.’

In other words, if you are facing a Saddam-type enemy – who doesn’t have nuclear weapons and who is not invading your home nation – they are not going to believe it if you threaten them with dozens of 100-kiloton nuclear warheads, each of which could destroy an area the size of Central London.

What you need instead, according to Rifkind, is the ability to threaten another Saddam with a single ‘low-yield’ (Hiroshima-size or smaller) warhead. That would be ‘credible’.

What’s ‘vital’?

Rifkind talked about using a single-warhead Trident missile to defence ‘our vital interests’. There were some peace researchers who said: ‘Oh, that’s just code for “the British homeland”.’

“It is therefore important for the credibility of our deterrent that the United Kingdom also possesses the capability to undertake a more limited nuclear strike in order to induce a political decision to halt aggression by delivering an unmistakable message of our willingness to defend our vital interests to the utmost.” - Malcolm Rifkind

Not so.

Two years later, Rifkind’s 1995 defence white paper talked about deterring or defending against ‘external aggression against the United Kingdom, our Dependent Territories or our vital national interests’.

It was clear that ‘our vital interests’ were separate from the UK homeland, its colonies abroad, or British allies.

Labour’s 1998 strategic defence review (SDR) repeated this: ‘our vital interests are not confined to Europe. Our economy is founded on international trade.... We invest more of our income abroad than any other major economy.... Foreign investment into the UK also provides nearly 20% of manufacturing jobs. We depend on foreign countries for supplies of raw materials, above all oil.’

That same SDR also said that Britain’s nuclear arsenal, its ‘deterrence requirements’, did not depend on the size of any other country’s nuclear arsenal, ‘but on the minimum necessary to deter any threat to our vital interests.’

If we put those two paragraphs together, that means that the UK needs the right number and type of nuclear bombs to protect its international trade and its investments abroad, as well as the flow of foreign investment and raw materials, ‘above all oil’, into the UK.

‘Vital’ and ‘core’

In 2021, the Integrated Review said: ‘Since 1995, France and the United Kingdom, Europe’s only nuclear powers, have stated that they can imagine no circumstances under which a threat to the vital interests of one would not constitute a threat to the vital interests of the other.’

In 2023, the Integrated Review Refresh said: ‘The UK’s aim is to establish regular strategic-level dialogues to build confidence and transparency around security ambitions, vital interests and military doctrines. During the Cold War, such mechanisms gave all parties a higher level of confidence that we would not miscalculate our way into nuclear exchange’.

Both these documents link ‘vital interests’ with nuclear weapons.

This year’s Integrated Review Refresh document used the phrase ‘core national interests’ four times. It said that Britain would prioritise its efforts in the places which ‘will be most consequential for our core national interests and international order’. In order of priority, these were: ‘the Euro-Atlantic, the Indo-Pacific, and our wider neighbourhood.’

The Integrated Review also talked about sea lanes: ‘Much of the UK’s trade with Asia depends on shipping that goes through a range of Indo-Pacific choke points. Preserving freedom of navigation is therefore essential to the UK’s national interests.’

This emphasis on securing sea lanes was also found in Rifkind’s 1995 defence white paper, which said: ‘We have global interests and responsibilities.... As a nation, we live by trade and investment.... The bulk of our trade, 92% by volume and 76% by value, is transported by sea, 64% by value with non-European Union countries. Our manufacturing industry is dependent on raw materials from overseas. Our global investments are estimated to be worth around $300 billion.... So we depend upon a stable environment within which to trade.’ (emphasis added)

Transparency

At this moment, the peace movement is not strong enough to overturn the Rifkind Doctrine. However, we can take some first steps: force the government to be a bit more transparent about its nuclear doctrines, and begin mobilising public opinion against these shocking policies.

Our invitation to you, dear reader, is to write to your MP (ideally by hand) asking her or him to ask the ministry of defence some questions based on the text below. Please feed the answers you get back to us!

------------

Dear MP,

The Ukraine War has raised the frightening possibility of nuclear weapons being detonated in conflict for the first time since Nagasaki.

I notice that in the Integrated Review Refresh, published in March, the government said: ‘The UK’s aim is to establish regular strategic-level dialogues to build confidence and transparency around security ambitions, vital interests and military doctrines. During the Cold War, such mechanisms gave all parties a higher level of confidence that we would not miscalculate our way into nuclear exchange.’

Please would you ask the secretary of state for defence the following questions to help provide me and the public with reassurance that the government is doing what it can to reduce the risk of nuclear miscalculation. If you could relay the minister’s replies to me, I would be grateful.

- Has the UK established ‘strategic-level dialogues to build confidence and transparency around security ambitions, vital interests and military doctrines’ (mentioned in the Integrated Review Refresh 2023) with any foreign nations? If so, how many? Can the minister name any non-NATO members involved in these dialogues?

- According to the Integrated Review 2021, there is a classified national security risk assessment (NSRA) which lists and assesses ‘the impact and likelihood of the most serious risks facing the UK and its interests overseas.’ Can the minister confirm that the UK’s overseas ‘vital interests’ are identified as such in the NSRA, and the risks to them have been properly assessed?

- Have these overseas ‘vital interests’ been communicated to any foreign nations in order to give ‘all parties a higher level of confidence that we would not miscalculate our way into nuclear exchange’?

- Is it still the case that the UK’s nuclear deterrence requirements do not depend on the size of other nations’ arsenals ‘but on the minimum necessary to deter any threat to our vital interests’, as laid out in the 1998 Strategic Defence Review?

- Is it still the case, as the 1998 Strategic Defence Review also made clear, that the UK’s vital interests include international trade, British investments abroad, foreign investment into the UK, and the supply of raw materials, ‘above all oil’ (chapter 1, paragraph 19)?

- Is it still the government’s aim, as Malcolm Rifkind announced in November 1993, to possess ‘the capability to undertake a more limited nuclear strike in order to induce a political decision to halt aggression by delivering an unmistakable message of our willingness to defend our vital interests to the utmost’?