Cao Shunli (1961 – 2014) was a militant petitioner who died in police custody in March 2014. Petitioners in China, mostly women, bear the brunt of the country’s authoritarian capitalism. Deprived of jobs, houses or land, they are trapped at the bottom of the social hierarchy. When they appeal to authorities for help, they are instead subjected to torture and arbitrary detention. In the bid for legal justice and economic solutions, Cao believed petitioners should exercise their political rights. My drypoint prints attempt to reenact the moments when Cao fought consciously against her fate.

1. Game of State

1. Game of State

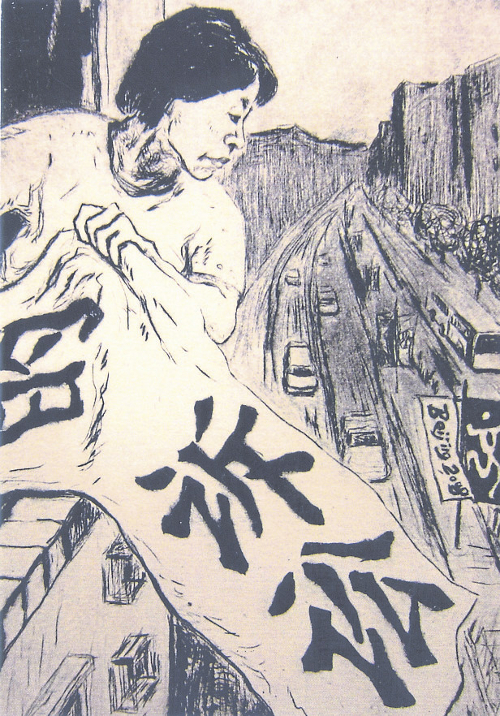

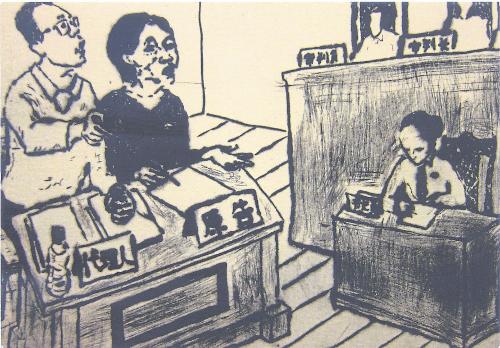

In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic games, a 20-metre-long banner was draped from a residential building along one of the busiest streets in Dongcheng District. The banner read: ‘Ministry of Human Resources Must Act in Accordance with Law and Accept My Arbitration Application; Beijing Intermediate People’s Court Must Act in Accordance with Law aand Accept My Lawsuit’. Cao Shunli, the creator of the banner, had campaigned for equal housing rights for more than a decade. In the early 1990s, she began to expose the corruption involved in housing privatisation. As a result, she lost her job as a civil servant at the ministry of human resources. All her social security benefits were taken away and she was detained twice.

2. Wild Grass

2. Wild Grass

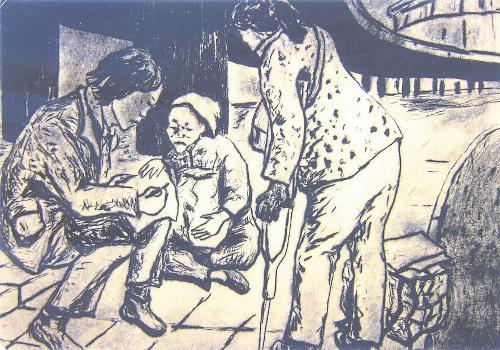

Cao Shunli met other petitioners and used her own legal background to help others in their fight for justice. Many petitioners will travel across the country to Beijing and stay in temporary shelters near the South Railway Station, close to a collection of government buildings including the national visit and letter bureau, the state council office, the national people’s congress and the supreme court. In the run-up to the Olympic games in 2008, the government demolished the shelters and cleared out all the petitioners. By autumn that same year, the petitioners had returned and were congregated again around the railway station.

3. Deep in Winter

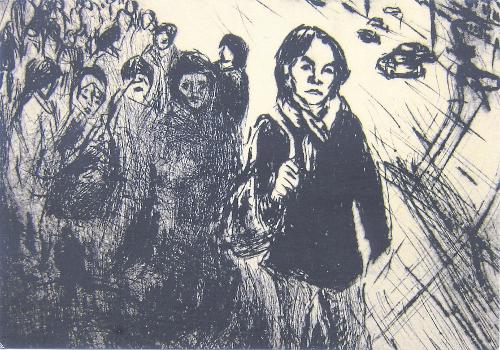

With a master’s degree in law from Beijing University, Cao Shunli was able to draw on her broad knowledge of international laws to challenge the domestic legal system. She had translated over 1,000 pages of international human rights legislation. When she learned that the UN’s new universal periodical review mechanism required member states to consult civil society in presenting the state human rights report, she submitted an application to the ministry of foreign affairs and the state council demanding participation in the UPR process. Without a reply after two months, Cao and fellow petitioners organised a ‘Walk for Rights’ in February 2009. They took to the street, believing it was better to walk than to wait.

4. Iron House

4. Iron House

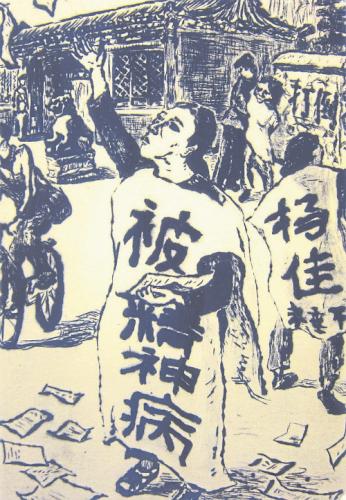

In March 2009, Sun Dongdong, a law professor in Beijing University told the media that ‘99 percent of petitioners are mentally ill’. This statement triggered waves of protests outside the university. Not only were they infuriated by the insult, petitioners also feared that, as Sun was involved in revising mental health laws, his remark could signal the legalisation of the existing practice of using involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation to persecute activists. Protesting outside her alma mater, Cao was arrested and sentenced to a year of ‘re-education through labour’ (RTL).

5. Absence of Justice

5. Absence of Justice

Cao was released on 11 April 2010, only to be sent back to RTL two weeks later on spurious charges, which served the purpose of preventing her from voicing dissent at the Shanghai World Expo. In detention, Cao filed a lawsuit against the Beijing RTL commission. Her appeal in court was strong and clear, but her case was doomed from the beginning in a country without an independent legal system.

6. Flesh vs Uniform

6. Flesh vs Uniform

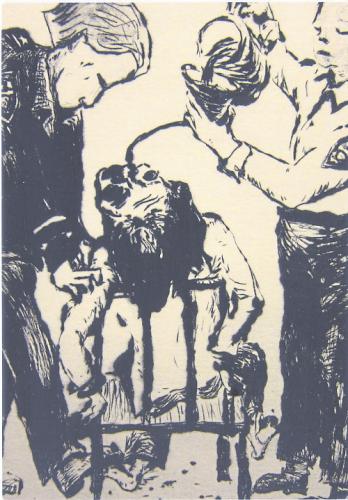

Torture and ill treatment are widely practiced in detention in China. Detainees who dare to show any sign of disobedience are subjected to even crueler punishment. Cao was denied food for five days, and then forcibly nose-fed. Later, the ‘expense’ of her torture would be deducted from her allowances. In July 2011, when Cao was released at the end of her 15-month term, her health was severely compromised. Ironically, in the same month, the government published its assessment report stating that the goals as set out in the first national human rights action had all been achieved successfully.

7. Resistance of the Body

7. Resistance of the Body

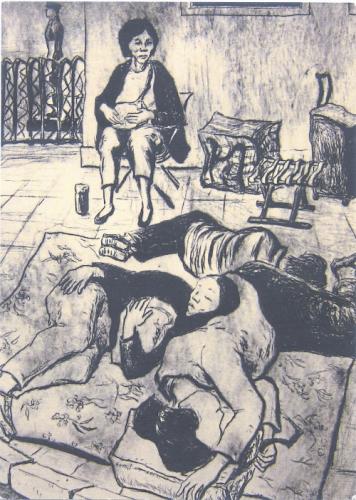

Soon after her release, Cao devoted herself to exposing torture in detention. She took other petitioners to visit RTL camps and collected testimonies from thousands of former detainees. The petitioners also submitted a government information disclosure request to the ministry of foreign affairs, demanding transparency of the state report prepared for China’s second UPR at the UN. The ministry rejected their request on the grounds that such information held ‘state secrets’. On 18 June 2013, Cao and fellow activists, mostly women, staged a peaceful sit-in outside the ministry. It lasted several months, day and night, despite constant police harassment.